When considering Valentano to illustrate changes in Italian industrial districts, we note that the single most important transformation is that today we no longer find an independent entrepreneur - the impannatore - who organizes a complex production process shared among a host of specialized micro firms. Firm size has increased, as we noted, and the coordination role has been assumed by the client itself, always leading luxury firms like, Gucci, Prada, Fendi, Céline. Valentano specializes in leatherworking, almost exclusively the assembly of semi-finished components for clients with global brand recognition. These components are furnished to local firms by the client who acquires this material using contractors in other parts of Italy. The components include the leather parts, the metal clasps, the chain handles, and all the elements required to assemble the handbag.

The components arrive at the contractor’s firm in numbered bundles, along with a silk ribbon with a set of individual product codes corresponding to the number of bags to be assembled. The numerical code is sewn into each handbag ensuring product traceability. A top priority for luxury firms – which are locally called ‘the brand’ (firma) - is to obstruct the creation of knock-offs. The unique product codes are the single most important component in the assembly process, ensuring that counterfeits cannot be mistaken for the authentic brand.

Further such assurance is provided by the high quality of the materials and superlative craftsmanship. The obsessive concern for brand security discourages the fragmentation of the production process, and is a key reason why firms today are of a larger size than the micro firms of the 1980s. Rather than having a host of micro firms coordinated by an independent entrepreneur, today two or three contractors take responsibility for producing the handbag in a process controlled directly by the fashion house. For this reason, in a system completely different from that of the 1980s, contractors involved in the process have no contact with contractors further up the production chain.

The client contracts the production services as the need arises, working often in small lots of one or two thousand units. The exact details of the production process are shared between the specific contractor and the fashion client. Handbags are a typical product, each requiring in final assembly a set of processes which span the duration of three days. The production rate and schedule are determined by the size and urgency of the commission, usually lasting a period of several weeks. Requirements vary considerably, but typically a contract for two thousand handbags, say, will span a period of some three months between planning and production. In this example, twenty workers handling the different phases of the finishing and assembly process can produce an average of fifty handbags per day.

The duration of each stage of the assembly process is calculated in minutes in a process negotiated between client and contractor, and the resulting schedule is circulated among the workers. The smallest sized team required to reach this production rate and standard comprises some twenty highly skilled workers. Yet given the small size and short duration of individual contracts, even small firms aim to secure more than one product commission at any given time. The ability to handle simultaneously multiple production operations determines the lower end of firm size, which is of about fifty workers. It should be noted that clients never negotiate long-term contracts, leaving the contractor in a state of perpetual uncertainty.

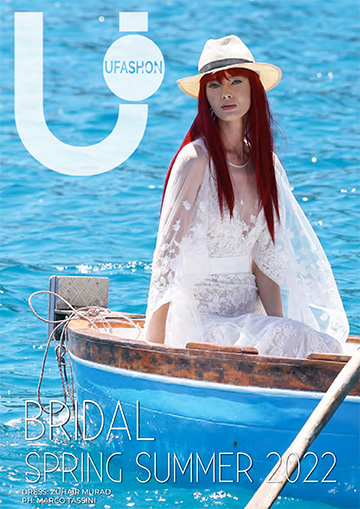

The contractor is under close scrutiny by the client, and is required to sign a regulation ensuring high artisan quality as well as product security in terms of discouraging counterfeits. These are not the micro firms of the 1980s, and have gross annual revenues in excess of one million euros. The entrepreneurs are themselves local artisans who started working in the leather trade for fashion brands in the 1990s.

Most come from a group of some twenty workers who began to operate in this sector in a makeshift workplace in the town’s cramped medieval center in the late millennial years. Later they separated and moved to the new industrial location. These artisan-entrepreneurs are familiar with the intimate details of all the processes involved in finishing the component parts and assembling the handbags. Their most pressing concern is securing qualified personnel in the absence of any local training program. They hire young workers, mostly women, on apprenticeship contracts which are used until the worker turns 29 and is hired on a standard contract. Entrepreneurs are protective of their workers.

It takes at least five years for an apprentice to acquire the skills required to work autonomously.

The entrepreneurs themselves take leadership in training these workers, who earn about €1,400 net a month, a high salary by the local standard. Some apprentices may not complete the training program, and this is a significant loss for the firm. One entrepreneur expressed concern over the risk that a competitor might ‘steal’ a worker by offering a higher salary. Skilled workers are the production bottleneck.

Equipment is not a major limitation, and is often obsolete. The prevailing machinery comes from the Italian north, especially OMAC, as well as Japanese Juki machinery. Some firms use advanced robotic techniques, but the consensus is that the manual regulation of equipment best suits the needs of the artisan process. The workspaces are clean, luminous, and well-ventilated, with high-standard service area. There is a strong sense of comradery, and many workers are related to one another, at times as relatives of the entrepreneur. Relations with trade union representatives are excellent, and unions are seen as allies to the firm, especially in helping navigate Italian labor regulations.

The client firm has decisive control over the business activities of the contractor, even asking to see the contractor’s balance sheets before signing a contract. The clients want to be certain that the contractor will cover their operating costs. One entrepreneur claimed that brands wish also to limit the contractor’s earnings, in order to inhibit their ability to establish their own products for direct sale to the market. Indeed, none of the firms in Valentano produce for direct sale. One group of local entrepreneurs attempted to create their own handbags, but the products were expensive, lacked brand recognition, and the venture failed.

The asymmetry between client and contractor is also seen in the division of revenues deriving from the sale of the final product. The contractor’s share is about three percent of the price paid by the end consumer for a luxury handbag. The advantages to client firms are obvious, since with low costs and no liabilities they can publicize their handbags as being made entirely in Italy. Yet asymmetry notwithstanding, local contractors survive and represent significant opportunities for local employment. A final question arises concerning the location of these districts.

Valentano is a somewhat isolated case of an industrial district in Lazio. It came into being owing to proximity to the southern Tuscan industrial district of Piancastagnaio, about an hour north by car. The contacts and skills needed to launch the Valentano industrial district in the 1990s come from this source.

The Covid epidemic has had major negative impact on balance sheets, with up to fifty percent losses. Yet notwithstanding this reversal one senses optimism concerning the future. These much-transformed heirs to the Italian industrial districts of the 1980s are significantly different from those described by Andrea Saba in the early years. The most salient difference is the asymmetry between client and contractor which limits margins for entrepreneurial innovation.

But the system continues to represent the excellence of Italian artisan work in the context of a highly structured modern market. Entrepreneurs are rightly proud of their ability to maintain the local industrial system. It not only provides work for citizens, and revenues for local government, it also allows entrepreneurs to be active in supporting the local community in multiple spheres, from sporting activities to cultural events. Bruno Prota is the owner of an important local firm, New Life. He is an excellent example of the same values that drove industrial districts in the 1980s: strong independence, expert entrepreneurial skills, consummate mastery of the leather working craft.

He has faced many challenges in over thirty years of professional activity. Today the hurdle is surviving in the deeply structured modern fashion market, a challenge he faces with his characteristic flare and determination. He notes that a key area where the public sector could provide more support is in artisan training programs.

Such training programs are already well-established in Tuscan industrial districts. Now is the time to encourage the extension of these services to competitive local territories like Valentano.

Gregory Overton Smith

D.Phil. Oxford

Temple University Rome