My friend Andrea Saba was one of the first economists to publish work on the Italian industrial district.

He joined penetrating insight to a wonderful sense of humor. An anodyne example of this is found in the story he used to tell of how when visiting the USA for a lecture tour in the 1980s, he adopted the metaphor of the bumble bee to explain Italy’s extraordinary industrial growth in that period.

The bumble bee, he noted, was shown by NASA to be technically incapable of flying, owing to the small wing size in proportion to the huge body mass. Yet the bumble bee flies nonetheless, Saba opined, only because it ignores the laws of aerodynamics. Similarly, Italian economic prosperity in those days defied all expectations: notwithstanding many woes, the country outdistanced Britain in 1987 to become the sixth most powerful economy of the world.

Saba claimed that the industrial districts which propelled this growth were a continuation of Italy’s informal economy, which he ventured was not entirely baleful in terms of national economic performance.

Informality unleashed bountiful experimentation, especially in the localization of industrial activities which by the 1980s were celebrated as the industrial district. These districts not only spurred economic growth, they also gratified Italy’s historic individualism. Informality engendered the emergence of localized industrial systems with scant support from major financial institutions, be they state or private.

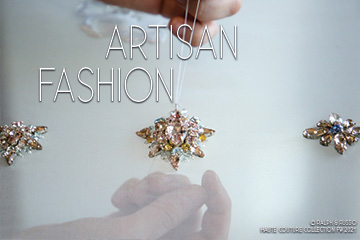

These early districts were the result - in Saba’s characterization - of heroic action undertaken by free men and women who had no resources other than peerless artisan skill and entrepreneurial audacity. Inevitably, many circumstances have changed over the last forty years. These changes chart a course marked by hazards which have caused the Italian bumble bee to struggle in an increasingly crowded global arena. Yet industrial districts continue to play an important role in the nation’s economy.

Official statistics (ISTAT) estimate that about a third of all industrial production takes place in these localized economic systems. According to these same data, in 2011 there were 141 industrial districts in Italy, a significant number, although in decline as compared to 2001 with the loss of forty districts. These localized economic systems operate in the areas for which Italy is world famous, like motors and machinery, textiles and cloth, home building materials and furnishings, leather and shoes. Saba illustrates how historically these districts were comprised of highly specialized independent micro firms working in collaboration with other such firms in a system which ensured individual and territorial success.

These micro enterprises did not sell directly to the market, but rather produced superlative components which were part of a complex supply chain. The small size of the enterprises allowed each to develop unmatched expertise in a particular production process, leveraging the advantages of flexible specialization. But diminutive size was not only a response to changing production requirements, it was also a response to Italy’s labor laws that were given formidable strength by legislation of 1970. This took the form of a package of laws incorporated into the Italian constitution which severely limited the ability of an enterprise to shed labor, and at the same time gave powerful support to trade unions.

These provisions, however, did not apply to firms with fewer than 12 employees, constituting a major incentive for entrepreneurs to invest precisely in small enterprises. Labor laws have changed today under the influence of neoliberal economic policy orientations, watering down public support for workers and trade unions, and eliminating the advantages of micro firms from the standpoint of labor flexibility. Another significant change is found in the market itself, with the resolute consolidation of a few leader firms in the economic areas where Italy has always excelled, leaving little opportunity for real competition. Italian industrial districts, like all industrial production, is concentrated in the north.

Few localized production systems have been successful in other parts of the country, with noteworthy exceptions. For instance, in Lazio Region, of which Rome is the capital, only one industrial district is recognized by official statistics, and that is Civita Castellana, a territory specialized in ceramics production. Yet statistics never tell the full story, and in the northern part of Lazio one finds an important if unrecognized industrial district in the municipality of Valentano. This is a spectacular medieval town with an extraordinary history.

Its outskirts are equipped with an industrial area specialized in leatherworking where some twenty industries employ 400 workers - a significant number by the local standard.

The single firms are large by comparison to those of Italy’s industrial districts in the 1980s, having a workforce ranging from forty or fifty workers to over two hundred. The larger productive capacity of these individual firms can in part be attributed to changing labor laws. But it is also a response to the current relationship between the client firms – all global fashion brands - and local contractors.

In the 1980s each small firm took responsibility for a single process complementing those of other specialized contractors, all coordinated by an entrepreneur (called the impannatore) who took responsibility for consigning the finished product to the client.

This model no longer prevails in Valentano, furnishing a case study which can help us understand significant transformations in Italian artisan production.

Gregory Overton Smith

D.Phil. Oxford

Temple University Rome